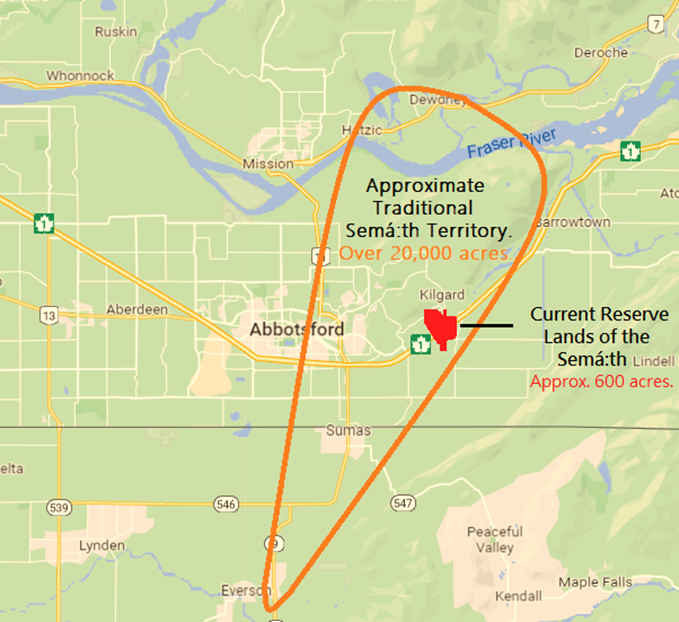

Semá:th nation bounds and time immemorial possession of the land

The Semá:th are a part of the broader Stó:lō Nation and have had stewardship of their traditional lands since time immemorial. These lands cover the eastern side of the settler city of Abbotsford extending down into the states following the Sumas River and over the Fraser River onto the coastal mountains.[1] This territory has been in the same approximate form for the last 11,000 years and the Semá:th had long thrived on these lands and the Sumas Lake that was found in this territory.

Today in the lower mainland the most important river is often considered the Fraser. However, the Nooksack, the Sumas, and the Chilliwack Rivers were what created and sustained Sumas Lake. It is likely that the head of the Sumas River was also where the largest Semá:th village was located.[2] The Semá:th lived in this region for 7,000 years before the European settlers moved into the region.

The colonists arrived in the late 19th century and originally lived in relative peace with the Semá:th who often found it profitable to guide the settlers who needed help gaining access to the area and travelling through the Lower Mainland. However, the European diseases that the settlers brought with them did significant damage to Indigenous communities like the Semá:th. Under the colonial government of Joseph Trutch, the remaining Semá:th were forced onto a reserve that was separated from the resources that they depended on.[3]

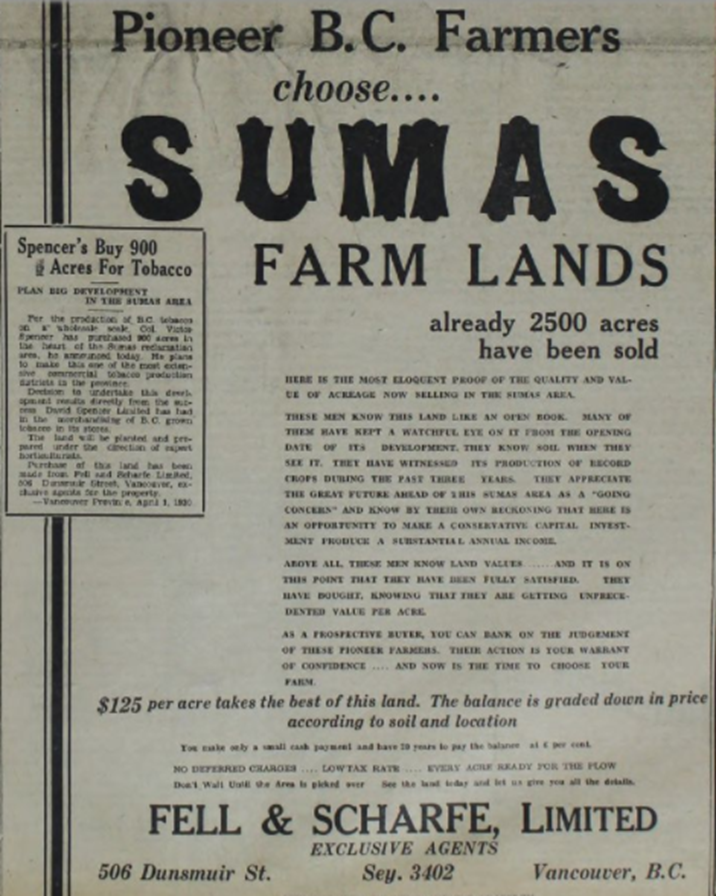

One of the main goals of the Abbotsford settlers was to drain Sumas Lake and, in their mind, ‘reclaim’ the land that they saw as being wasted. However, they did not stop to consider that this would also be damaging an important ecosystem and depriving the Indigenous community of their traditional way of life.[4] This occurred just before the Great Depression with the draining happening from 1920 to 1924. For the Semá:th the Depression meant watching their traditional lands being sold off to incoming immigrants, mostly the Mennonites, as farmland; watching the colonial government grow rich from the sale of their lands while struggling on the reserve lands they’d been forced onto.

The Lake

The Semá:th thrived because of the Sumas Lake, known to them as simply the Lake.[5] This ended when they were forced onto a reserve that was only 3% of their original territory. Further, Sumas Lake was the main source of food for the community of 10,000, providing 85%.[6]

Sumas Lake would be drained by the European settler community in the mid-1920s and the Semá:th fully lost access to this important resource.[7] The resulting lakebed was sold as ‘recovered land’ to immigrants who were looking for farmable land.

Effects of the depression on the Semá:th?

The Great Depression would affect the Semá:th but less directly than it would on the European settlers. Instead of a stock market crash causing struggles for the community, it was the settler government. First, as mentioned above the Semá:th were forced onto a small reserve that was not capable of providing for the entire community. Another issue that would harm the Semá:th was the lifestyle rules put in place by the paternalistic settler government and the fines for breaking them. For example, during the Great Depression, public drinking and/or intoxication was illegal and punished by a fine. The local papers record how this fine had been used, showing that when visiting Americans are caught drinking in public they were fined less than what the Semá:th were fined for the same offence.[8] The reasoning behind the difference in fines was later explained in an ad that reminded travellers that both Indigenous peoples and children were not allowed to be given alcohol.[9]

These rules show not only the way that the settler government thought about the Semá:th Nation but also the extent of damages that were enflicted by this government.

Click here for a bibliography for this page. Click here for a full website bibliography.

[1] “About Sumas First Nation.” Sumas First Nation, 2022. http://www.sumasfirstnation.com/.

[2] Chad Reimer. Before We Lost the Lake: A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley. Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2018.

[3] Chad Reimer. Before We Lost the Lake: A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley. Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2018.

[4] Chad Reimer. Before We Lost the Lake: A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley. Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2018.

[5] Chad Reimer. Before We Lost the Lake: A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley. Halfmoon Bay, BC: Caitlin Press, 2018.

[6] Gomez, Michelle. “Sumas First Nation Built on Higher Ground, Unaffected by Flooding in Former Lake Bed, Says Chief | CBC News.” CBC News. CBC/Radio Canada, November 20, 2021.

[7] “Arts & Heritage.” City of Abbotsford, 2022.

[8] Heller, Gerald H., ed. “Two Americans Found Intoxicated.” Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. March 5, 1930. and Heller, Gerald H., ed. “C Commodore Vedder Crossing and D Antone Nooksack were each fined… ” Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. January 8, 1930.

[9] Heller, Gerald H., ed. “10 Don’ts for Tourists and Others.” Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. April 24, 1930.