The Abbotsford Lumber Mill

The most notorious owners of the Abbotsford Lumber Company were the Tretheweys. However, there were two owners before the Tretheweys gained control. Professor Charles Hill-Tout was the creator of the colonist lumber mill before he sold it to the group known as Cook, Craig, & Johnson. Both of these owners kept their logging operations relatively small and did not expand significantly.

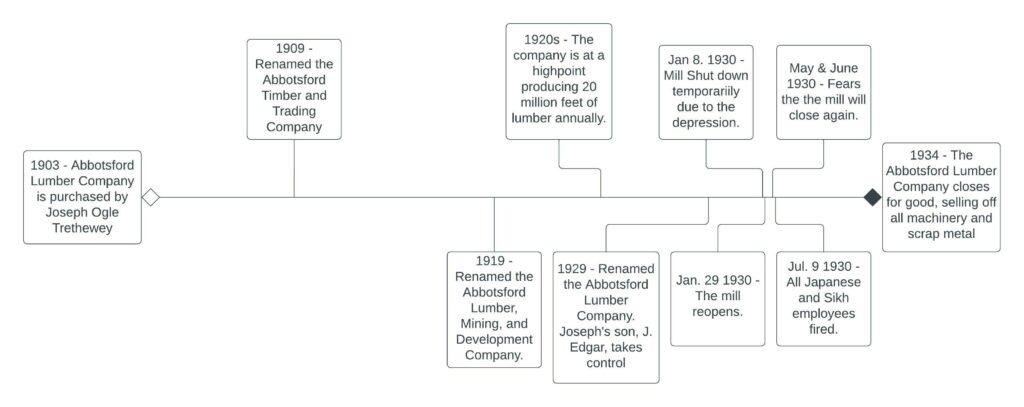

After these two owners, the Trethewey family purchased the Abbotsford Lumber Company in 1903 with Joseph Ogle Trethewey becoming the primary owner and Arthur Trethewey taking the role of president.[1] In 1909 it was renamed the Abbotsford Time and Trading Company. The Tretheweys would change the name of their company again, this time to the Abbotsford Lumber, Mining, and Development Company, in 1919 with Joseph as the new president and Richard Trethewey as the mill manager. This was the time when the company was the most productive and the workers were able to produce “20 million feet of lumber and between 15 and 20 million shingles annually”.[2] It was the single largest employer in town and among the largest employers in the province”.[3] At the beginning of the Great Depression, 1929, the name was switched back to the Abbotsford Lumber Company and Joseph’s son J. Edgar Trethewey took over as President. As mentioned, the Abbotsford Lumber Company was one of the main sources of employment for the village of Abbotsford. Following this, from 1900 to the early 1930’s Abbotsford was a logging town and then with the depletion of lumber and the draining of the lake, it transitioned to a farming space.[4]

The Tretheweys

The Trethewey’s are remembered positively by many in Abbotsford as the timber baron family that was, according to the City of Abbotsford, “instrumental in the early development of Abbotsford” and well known for their philanthropic community spirit (Donald Luxton, “Statements of Significance 2005-2006, page 3). The family was certainly powerful, owning 103.97 out of the 160 acres that were classified as Abbotsford in the 1930s as well as significant holdings in the rest of modern Abbotsford, but many historical sources do not show a ‘philanthropic community spirit’ at least not towards all members of their community (Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co.). This is despite the narrative that has often been emphasized – about their donation of lumber to South Asian and Japanese employees for cultural buildings (the Gurdwara and a bath house) – over the more nuanced truth.

One study shows that the Trethewey’s considered their mill a safe space to work but through the time of their ownership the papers, even outside of Abbotsford, are filled with reports of death and injury to their Japanese workers who were given the most dangerous jobs at the mill (Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co. and several newspaper articles from the Abbotsford Post, the Abbotsford Sumas Matsqui News, and the Vancouver Sun). This difference in the perception that the Trethewey’s promoted, and the reality of how different racial communities were treated at the lumber company is clear. Further, the family terminated the employment of all Japanese and South Asian workers when the Great Depression slowed the logging business.

The treatment of the diverse communities employed at the Abbotsford Lumber Company along with other information that has come out recently, such as KKK involvement from members of the family, show that while they may be known for their role in the growth and development of Abbotsford and community acts, they were mainly interested in helping the group of European Colonists and furthering their own economic pursuits.

Diversity at the Mill

The Abbotsford Lumber Company was the largest single employer in the Abbotsford area and employed a diverse population. This included European, Japanese, and South Asian settlers. As the Abbotsford mill was built away from Abbotsford proper it needed its own housing, and the Trethewey’s built separate boarding houses for each of these three groups.[5] This site was known as ‘Milltown’.

These groups were given different pay rates by the Abbotsford Lumber Company based on race with the Europeans being given the highest wage.[6] Not only were the Europeans given higher wages but also relatively safer positions. The Japanese in particular were given the most dangerous roles at the mill and were frequently injured or killed at work.[7] Further, as the Great Depression hit and the production of Canadian lumber dropped by 50% the first group that was let go from the Abbotsford Lumber Company were the Japanese and South Asian to preserve white jobs.

The Effects of the Depression

From 1929 on into the Great Depression the amount of work available at the mill dropped significantly because of both the aforementioned depression but also as they had logged almost all of what had been available in the area. By 1934, the Trethewey’s gave up on the lumber company and sold off everything of value.[8] A timeline of the Abbotsford Lumber Company during the depression can be seen here.

For many European immigrants, the Great Depression meant that times would be more difficult and that inflation would make it more difficult to provide for their families. For immigrants of non-European origin and the Indigenous community, the Great Depression brought the same economic concerns, but also an increase in racially based hatred. In Abbotsford, this was particularly true for those of Japanese origin as they became ‘scapegoats’ for the struggles that European immigrants were facing.[9]

This hatred led to the local officials from Matsqui, Sumas, and Abbotsford and at least 25 local businessmen meeting with the Abbotsford Lumber Co. to ask that all available jobs be given to the European immigrants.[10] Soon after, in early July 1930, the Japanese and South Asians were fired en masse by the Abbotsford Lumber Co. This meant that the economic effects of the Great Depression would be felt most significantly by the non-European immigrants. After the Abbotsford Lumber Company fired these populations many of them found that the only available work was to transition from logging to farming, though this is not an easy field to gain financial success from without a large initial investment.

Click here for a bibliography for this page. Click here for a full website bibliography

[1] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake: The Trethewey Brothers and The Abbotsford Lumber Company.” (The Forest History Association of British Columbia, October 1996), 2.

[2] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake: The Trethewey Brothers and The Abbotsford Lumber Company.” (The Forest History Association of British Columbia, October 1996), 2.

[3] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake: The Trethewey Brothers and The Abbotsford Lumber Company.” (The Forest History Association of British Columbia, October 1996), 2.

[4] “Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co. and the effects on the local community”. (Immigration & Settlement Russian Immigration Profile 2006, Notes and Information. The Reach Gallery Museum, Abbotsford), 1.

[5] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake: The Trethewey Brothers and The Abbotsford Lumber Company.” (The Forest History Association of British Columbia, October 1996), 2.

[6] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake”, 2.

[7] “Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co. and the effects on the local community”. (Immigration & Settlement Russian Immigration Profile 2006, Notes and Information. The Reach Gallery Museum, Abbotsford), 6.

[8] MSA Museum. “Milltown To Mill Lake: The Trethewey Brothers and The Abbotsford Lumber Company.” (The Forest History Association of British Columbia, October 1996), 2.

[9] “Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co. and the effects on the local community”. (Immigration & Settlement Russian Immigration Profile 2006, Notes and Information. The Reach Gallery Museum, Abbotsford), 8.

[10] “Joe’s Town: A study of the Abbotsford Lumber Co. and the effects on the local community”. (Immigration & Settlement Russian Immigration Profile 2006, Notes and Information. The Reach Gallery Museum, Abbotsford), 9.