Japanese Immigration and Restraints

Starting in the 1880s Japanese people began immigrating to Canada and British Columbia and they worked in lumber milling, railroad construction, and fish canning before gradually moving to farm production.[1] This worked well as most of the immigrants came from the farming and labour classes of Japan and were well prepared for the kind of work that they assumed.[2] For many, an immediate goal was to purchase their own land with 30% managing to purchase on arrival. Those who could not purchase immediately often diligently saved income in an attempt to become a landowner. [3] However, the relative success of the Japanese immigrants became threatening to the European settlers who quickly took action to restrain the competition of this group.

Between 1906 and 1908 9,000 Japanese immigrants arrived in Canada. By 1907 Canadian officials entered into an unofficial agreement with Japan that only 400 men would be allowed to immigrate to Canada annually, meaning that the majority of immigrants after this were women. This seemed sufficient to many, however, by 1923 this was restricted again to 150 males annually and then in 1928 to 150 total Japanese people.[4]

It seems that for many of the original white settlers even 150 legal immigrations per year was too much, in 1935 an article titled “Peaceful Conquest of B.C. By Japanese” claims that the “white child born today has no future in this province”.[5] While this was an overstatement it shows the fears that fed into political and economical actions taken by the white settler government. This article told its audience that the Japanese were buying fake birth certificates and having enough children that despite the rule of 150 immigrants per year the Japanese population is growing by more than 2000 people a year. These propaganda statistics are meant to incite fear in the white settler population, making them believe that their culture would be wiped out. This plan was likely successful as the Abbotsford Post included articles defending limitations and costs of immigration when some from the East Coast spoke out on the issue.[6]

The fears that were being fed by the newspaper were capitalized on by the politicians. This is particularly visible in the political platform of Henry J Barber, which promised to decrease ‘Oriental Immigration’, ‘Japanese Immigration’, and create a better ‘Immigration Policy’.[7] These policies were clearly received well as soon after this ad was run it was confirmed that Barber had won his seat by a majority.[8] The results of this election help to show the opinions of the voting class in Abbotsford at this time.

Migration of the Japanese from Vancouver to Abbotsford

Much of the immigration mentioned above originally occurred in the major urban areas such as Vancouver and Victoria. However, due to the tensions mentioned above the Japanese population would migrate from major areas beginning in the early twentieth century. Discriminatory restrictions and treatments in these major urban areas helped to increase the immigration to Abbotsford and other parts of the Fraser Valley. Soon after these regulations were enacted the highest population of Japanese Farmers in BC was in the Fraser Valley, and many owned at least a partial share of farmland. However, even when they had their own farmland, they would often supplement their income with work at mills, particularly through the winter.[9]

Treatment in Abbotsford

The 1935 thesis, written by Rigenda Sumida, said that the relationships between white settlers and the Japanese community were good and non-discriminatory, at least in comparison to the tensions found in the fishing industry. Particularly, the author pointed to agitations being brought up only by certain members of the white settler community and not being felt by the majority of white farmers.[10]

This issue is difficult to come to terms with for a few reasons. We know that just five years before this thesis was published the Abbotsford Lumber Mill on the recommendation of Abbotsford, Matsqui, Sumas city officials and business owners fired the entire Japanese workforce to provide jobs only for the white community during the depression. Also, this thesis had already acknowledged that the Japanese farmers often also worked at the mill to provide extra income at the farm.[11] This makes it seem like the relationship may be being portrayed in an overly positive light, even within the context of the period. However, the distinction of farmers without saying their group means that the author may be looking at communities such as the Mennonite whom themselves faced discrimination from earlier settlers. If this is the case it makes sense that they might have been less swayed by propaganda against the Japanese, as the author claimed. Without having access to the sources used by this author it is difficult to say if this was an overly positive perspective that glosses over discriminatory practices or if there were in fact many supporters of the Japanese found in the farming community.

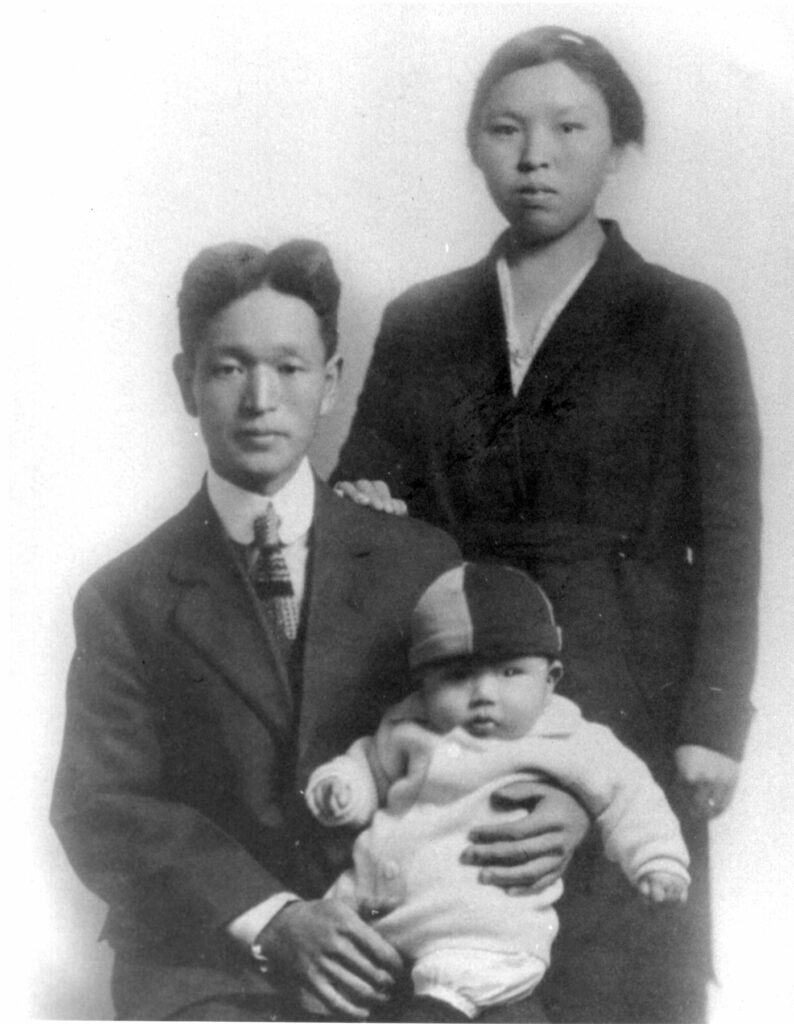

Riichi Sasaki [12]

Riichi Sasaki was a Japanese immigrant who like many immigrants was dedicated to the idea of finding and purchasing land that could support his potential family. He moved to Canada in 1907 and got a job at a Lumber Mill to make money. By 1910 Richard had earned enough to purchase 40 acres of farmland in Abbotsford. On this plot he built a home for his family. He would return to Japan in 1919 to find his wife, Misako Sasaki, and she arrived in Canada in 1920. Unfortunately, due to prejudices in World War II, the family would be forced to move away from the coast, to Alberta, by 1942 and they lost all of their land.

Misako Sasaki [13]

Misako Sasaki, the wife of Richard Sasaki, goes into more detail about what their life looked like at Clayburn. Misako tells of her journey to Victoria where she was picked up by her husband and immediately given Western style clothing for the remainder of the trip to Abbotsford. Following this she describes how when she first arrived in 1920 there was much to be done on their property and that there was not yet a thriving Japanese community. By the end of the 1920s there was a significant number of Japanese farmers in Abbotsford and despite struggles of the Great Depression the group had managed to build a combined Buddhist church and language school.

What the Japanese did in Abbotsford

The Issei (First Generation Immigrants) Japanese normally filled one or both of two roles in Abbotsford. They would either work for the Abbotsford Lumber Company or they would work in the farming industry. When working in the farming industry they would either work on their own plots of land or as labourers on another farm. Also, it is important to note that many of the Japanese would fulfill multiple roles in a concentrated effort to get ahead. This meant that many would work at the Abbotsford Lumber Company or as a labourer and cultivate their own land during the time that they had off.

Treatment at the Abbotsford Mill

At the Abbotsford Lumber Mill, the work was organized racially. All races had segregated living spaces, but the Japanese in particular were given a certain role in the production of lumber. This role was to sort the logs that had been cut and delivered to Mill Lake. When looking at records from the time it seems clear that this specific role that had been given to only the Japanese employees was more dangerous than other roles at the Abbotsford Lumber Mill.

The increased danger can be seen in the multitude of articles found in the local newspapers detailing the significant injuries and deaths of Japanese workers. These articles are not seen for the White or even the South Asian population that worked at the Mill. This shows that the role that was given to the Japanese community caused significant harm to the Japanese workers.[14]

All the acts taken against the Japanese during the time of the Great Depression show the significant prejudice and harm faced by the Japanese. These issues were caused not directly by the economic recession but by the fears of the white settlers and their government who saw this immigrant population as an economic and racial threat.

Click here for a bibliography for this page. Click here for a full website bibliography

[1] Thomas Perry, “Canadian Mosaic in the lower Fraser Valley” (1984).

[2] Sumida, Rigenda. “The Japanese in Agriculture” (1935), 277.

[3] Sumida, Rigenda. “The Japanese in Agriculture” (1935), 278.

[4] Anonymous. “Immigration Profile Overview.” Immigration and Settlement, Japan Immigration Profile 2006. The Reach Gallery Museum, Abbotsford.

[5] Heller, Gerald H., ed. “Peaceful Conquest of BC by Japanese” Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. February 27, 1935.

[6] John A. Bates. “No Title”, The Abbotsford Post, October 28, 1910, A3.

[7]Heller, Gerald H., ed. “Barber has Worked for the Farmer” Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. July 9, 1930.

[8] Heller, Gerald H., ed. “Barber Retains Seat by Large Majority”, Abbotsford, Sumas, Matsqui News. July 30, 1930.

[9] Sumida, Rigenda. “The Japanese in Agriculture” (1935), 285.

[10] Sumida, Rigenda. “The Japanese in Agriculture” (1935), 296.

[11] Sumida, Rigenda. “The Japanese in Agriculture” (1935), 330.

[12] Sasaki, Richard. “Richi Sasaki.” Immigration and Settlement, Japan Immigration Profile 2006.

[13] Sasaki, Misako. “Misako Sasaki: Recollections of Her Life in Clayburn”. Immigration & Settlement, Japanese.

[14] Bates, John A. “Met His Death”, The Abbotsford Post, July 21, 1911., Bates, John A. “A Bad Accident”, The Abbotsford Post, July 22,1910., and Bates, John A. “A Japanese Hurt”, The Abbotsford Post, September 23, 1910.